Indian History

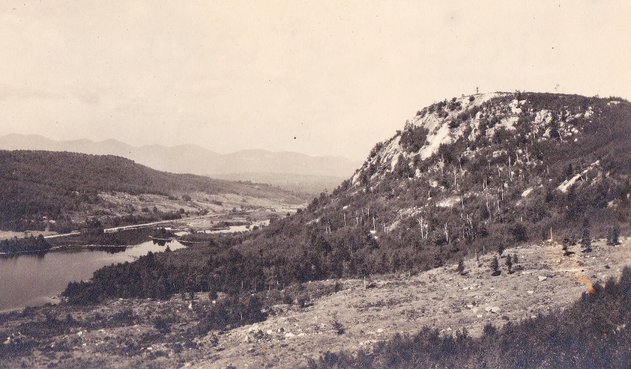

Mt. Jasper

The White Mountians, originally called the “White Hills”, were created when the North American Plate moved westward over the New England Hotspot. This took place around 124 to 100 million years ago. Widespread evidence of past glacial activity can be seen in the U-shaped form of various notches and round mountaintops. The ice sheet that covered Berlin, and the rest of the White Mountains, is called the Laurentide ice sheet. At some points, this glacier was 2 miles in hight and covered most of Canada and the northern part of the United States.

On June 4, 1642, Darby Field, an Irishman who was accompanied by two Indians, became the first white man to step foot in the “White Hills.” The journey lasted 18 days and he made the first assent of Mt. Washington. The Abenaki Indians believe the “great sprit” lives there, and no Indians stepped foot on there. They called this mountain “Agiochook” which means either “mountain of the snow forehead” or “home of the Great Sprit.”

The Abenaki tribes that visited Berlin were a part of the Eastern Abenaki branch. The most commonly known story about these Indians that visited Berlin is that of Mt. Jasper. Several hundred years after ice-sheets retreated from northern New England, approximately 11,000 years ago, small bands of hunters camped periodically in places along the headwaters of the Androscoggin River. As sources of chert are rare in northern New England and not easily accessible, hunters constantly searched for other stones in good supply that could be substituted for chert. Mt. Jasper and its outcrops of excellent raw material for making flaked tools passed unnoticed until 7000 years ago or 4000 years after exploration of the North Country.

The stone sought anciently at Mt. Jasper was rhyolite, a variety of igneous rock. Once found, its location was not forgotten until firearms and iron tools obtained in trade replaced stone weapons. In its heyday Mt. Jasper was visited regularly by Indians, at least every few years and

perhaps every season. The earliest quarrying at Mt. Jasper is marked by a series of shallow pits running along the strike of the rhyolite dike at the crest of the hill. There is no evidence that the Indians remained for long periods at Mt. Jasper because their work lasted only a few days.

The Abenaki used rivers as highways, as did many other Indians in that time.

Back then they had no major roads. There is an old story of a white man that was trading with the local Indians. The trader and an Indian were near the Berlin Falls when the trader realized he was out of bullets. The Indian, being a native of this area, knew where to find some lead. After 3-4 hours the Indian brought back a huge chunk of lead and possibly silver. It is believed that the Indian got the lead from the mountains between Berlin and Success, where in later years it was discovered by a hunter that there is a vein of silver but unfortunately the whereabouts of this vein is lost to history and still sits waiting to be rediscovered.

We know that there is a vein of silver somewhere in these mountains because this hunter sent the samples to New York to have them tested and the results where that it was somewhere between 70-90% silver. Unfortunately this man searched for this silver vein for the rest of his life but could not find it again. The Androscoggin River back in the day, was a massive Indian highway where the Indians would get on in Maine and go up the river until reaching the Dead River in Berlin than they would most likely stop at Mt. Jasper, behind the Berlin High School, and stay for a couple days

and continue their journey. This time they would go up the Dead River to Head Pond and continue to the Connecticut River and from there can go down to Connecticut or anywhere else for that matter. The Indians called the Androscoggin River Arosaguntacook.

Eastern Abenaki is a dead laguage, but in Western Abenaki the word for shelter is Alomsagw, so from there we get the reconstructed Eastern Abenaki word "Adrosagunw" which would make Arosaguntacook mean something like "place of rock shelters". The Abenaki word for the Dead River was Plumpetoosuc, which might mean "shallow, narrow river with swift current." An Abenaki elder from Ondanak, in Canada, contacted me a while back and told me that he remembered his grandfather tell him the Abenakis called a water fall in Berlin "Nahsahwahnpanjahlook" which he said meant "the breathing casscades." Could this be Berlin Falls?

On June 4, 1642, Darby Field, an Irishman who was accompanied by two Indians, became the first white man to step foot in the “White Hills.” The journey lasted 18 days and he made the first assent of Mt. Washington. The Abenaki Indians believe the “great sprit” lives there, and no Indians stepped foot on there. They called this mountain “Agiochook” which means either “mountain of the snow forehead” or “home of the Great Sprit.”

The Abenaki tribes that visited Berlin were a part of the Eastern Abenaki branch. The most commonly known story about these Indians that visited Berlin is that of Mt. Jasper. Several hundred years after ice-sheets retreated from northern New England, approximately 11,000 years ago, small bands of hunters camped periodically in places along the headwaters of the Androscoggin River. As sources of chert are rare in northern New England and not easily accessible, hunters constantly searched for other stones in good supply that could be substituted for chert. Mt. Jasper and its outcrops of excellent raw material for making flaked tools passed unnoticed until 7000 years ago or 4000 years after exploration of the North Country.

The stone sought anciently at Mt. Jasper was rhyolite, a variety of igneous rock. Once found, its location was not forgotten until firearms and iron tools obtained in trade replaced stone weapons. In its heyday Mt. Jasper was visited regularly by Indians, at least every few years and

perhaps every season. The earliest quarrying at Mt. Jasper is marked by a series of shallow pits running along the strike of the rhyolite dike at the crest of the hill. There is no evidence that the Indians remained for long periods at Mt. Jasper because their work lasted only a few days.

The Abenaki used rivers as highways, as did many other Indians in that time.

Back then they had no major roads. There is an old story of a white man that was trading with the local Indians. The trader and an Indian were near the Berlin Falls when the trader realized he was out of bullets. The Indian, being a native of this area, knew where to find some lead. After 3-4 hours the Indian brought back a huge chunk of lead and possibly silver. It is believed that the Indian got the lead from the mountains between Berlin and Success, where in later years it was discovered by a hunter that there is a vein of silver but unfortunately the whereabouts of this vein is lost to history and still sits waiting to be rediscovered.

We know that there is a vein of silver somewhere in these mountains because this hunter sent the samples to New York to have them tested and the results where that it was somewhere between 70-90% silver. Unfortunately this man searched for this silver vein for the rest of his life but could not find it again. The Androscoggin River back in the day, was a massive Indian highway where the Indians would get on in Maine and go up the river until reaching the Dead River in Berlin than they would most likely stop at Mt. Jasper, behind the Berlin High School, and stay for a couple days

and continue their journey. This time they would go up the Dead River to Head Pond and continue to the Connecticut River and from there can go down to Connecticut or anywhere else for that matter. The Indians called the Androscoggin River Arosaguntacook.

Eastern Abenaki is a dead laguage, but in Western Abenaki the word for shelter is Alomsagw, so from there we get the reconstructed Eastern Abenaki word "Adrosagunw" which would make Arosaguntacook mean something like "place of rock shelters". The Abenaki word for the Dead River was Plumpetoosuc, which might mean "shallow, narrow river with swift current." An Abenaki elder from Ondanak, in Canada, contacted me a while back and told me that he remembered his grandfather tell him the Abenakis called a water fall in Berlin "Nahsahwahnpanjahlook" which he said meant "the breathing casscades." Could this be Berlin Falls?

Maynesboro

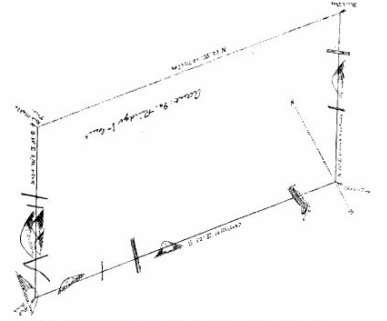

In 1771, land was surveyed under the orders of Governor John Wentworth. The township of Maynesboro, also spelled Maynesborough, started at a spruce tree at the southeast corner, a beech tree at the northeast corner, a rock maple tree in the northwest corner, and to a red birch tree in the southwest corner. All trees were marked with the letters M.B.P.B., which possibly stands for “Maynesboro Plantation Boarder”, but I’m not too sure.

The names of the grantees were, Sir William Mayne, Robert Mayne, George Gray, John Graham, Walter Kennedy, William Botts, Paul Wentworth, John Nelson, John Ward, Robert Graham, David Scrymgeour, Colin Mackenzie, Thomas Mayne, Edward Mayne, William Scrwens, Robert Needham, Samuel Smith, Thomas Evans, and William Wentworth. The grantees agreed that they would cut, clear, and make passable for carriages of all kinds, a road of 5 rods (82.5 feet) wide, at their own cost.

The names of the grantees were, Sir William Mayne, Robert Mayne, George Gray, John Graham, Walter Kennedy, William Botts, Paul Wentworth, John Nelson, John Ward, Robert Graham, David Scrymgeour, Colin Mackenzie, Thomas Mayne, Edward Mayne, William Scrwens, Robert Needham, Samuel Smith, Thomas Evans, and William Wentworth. The grantees agreed that they would cut, clear, and make passable for carriages of all kinds, a road of 5 rods (82.5 feet) wide, at their own cost.

|

The grantees also agreed that they would settle 15 families by January 1, 1774 and have 60 families living in Maynesboro by January 1, 1782. Every pine trees were to be cut and fit for the English Royal Navy, if any of the agreed upon were to be broken, they and their heirs would lose their grant in the township. As history shows, none of the grantees took up their grants and the Revolutionary War came, making any idea of the settlement of Maynesboro impossible by these grantees.

As our country we live in was young, taxes on Maynesboro were paid in the $1-2 dollar range. The next interesting thing I could find on early Maynesboro, was that of a deed for the sale of land on April 2, 1803. William Plumer owned large amounts of land in Maynesboro, which he used for hunting and fishing, and eventually Plumer’s Fort was named after him, which is now named Mt. Forist. Mr. Plumer sold this land to a relative named Samuel Plumer. The history of Maynesboro remained dull until William Sessions and Cyrus Wheeler came along in 1824 and built the first permanent home. |

|

Many people owned large amounts of land in Maynesboro before it

was organized as Berlin. Among the men who owned land were two brothers with the last name of Cilley. They owned some 40-50 lots, and one of these lots covered the top of the hill behind where White Mountain Lumber is today. Although they never permanently lived here, they often came to visit from Maine. On the very top of this hill were two large pine trees, called “the Cilley brothers”by the early inhabitants. These trees were very close to each other; and after land was cleared they were in plain sight. Around the first of February, 1838, one of these trees got blown down in a severe storm, and the remark was made “that one of the Cilley brothers must be dead.” At the beginning of the month of March, the townsfolk found out that Jonathan Cilley, who was a representative in Congress from Maine, got killed on Febuary 24 of that year in a duel near Washington D.C. with William J. Graves. “There,” said these wise ones, “we knew that the falling of that tree was a forerunner of Mr. Cilley’s death.” The other brother did not live much longer after that and in the settlement of their estate these lands were sold by auction at Portland, Maine, and were purchased by Daniel Green and Benjamin Thompson. |

Early Berlin Taverns and Hotels

The Mt. Forist House

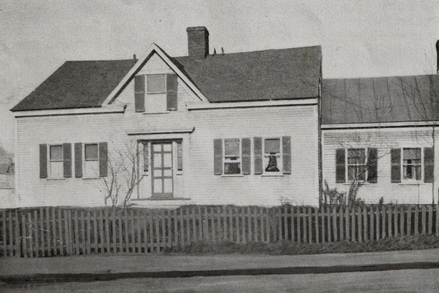

The Berlin Falls House or "Green's Tavern,"which stood on the site now occupied by the Rosenfield Block on Green Square, was built in 1830 or 1831 by Amos Green, a lumberman from Shelburne, for his private residence. This building was the first frame building in Berlin, before this there were only simple log homes. From the left of the tavern extended a storage shed, and some open wagon sheds, ending with a large barn on the corner of Exchange Street. It was a typical country tavern outfit. There is no record of public use of this building until 1850, when one James H. Holt, acquired the property and opened the "Berlin Falls House" to the public. A few years later, John Chandler, a blacksmith, and an uncle to the John Chandler of Dummer, who became a famous tavern keeper in that town, bought Mr. Holt out and continue the business for several years.

The Tavern got into the hands of Merrill C. Forist, who ran it for several years until it was obtained by Daniel Green, after the foreclosure of a mortgage. In 1874, Sullivan Green with his family returned here from Detroit, Michigan, to "keep house" for his father, Daniel. The tavern was closed as a public house. With business acumen for which she was noted, Mrs.Green, "Aunt Kittie," conducted a popular high-class boarding house until her old age caught up with her. Many families lived here until they could earn enough money to build or buy their own homes.

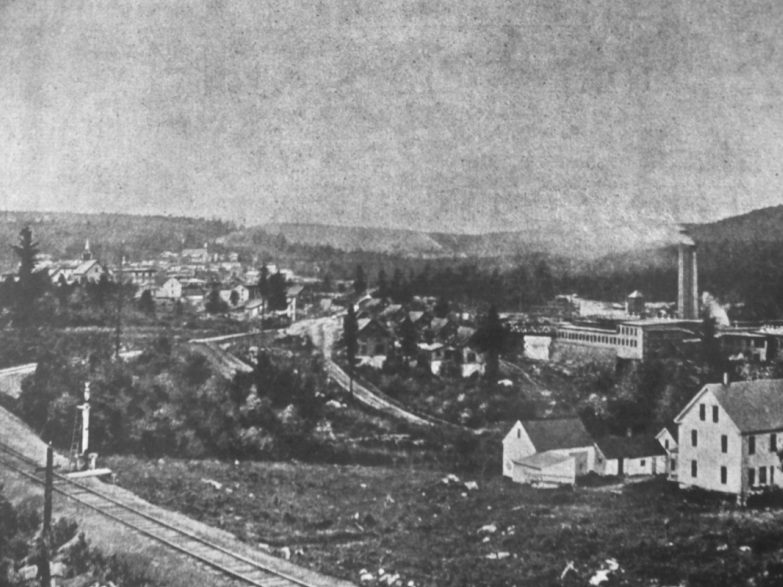

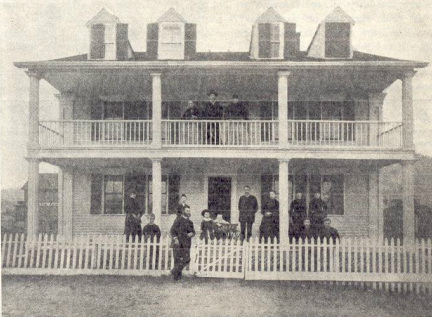

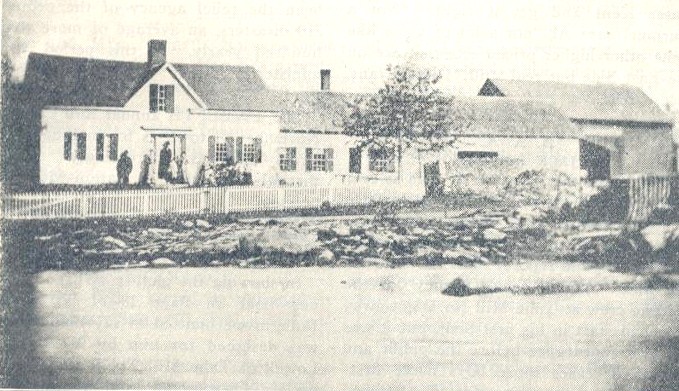

Now let’s turn our attention back to Merrill C. Forist. In 1866, Mr. Forist purchased a small cottage and made large additions for hotel purposes and opened the Mt. Forist House. It was located on rising groun a little back of the site now occupied by the new Bickford Place park. He continued this hotel until his death in 1879. The accompanying picture was taken from a spot on, what was then called, "the island," directly across the canal in back of Maureen’s boutique. In the photo, one can see the Androscoggin River running in front of the Mt. Forist House, the river once ran where those large green pipes are now (in back of Tony's Pizza), making the little parking lot where the bonfires after the Homecoming pride is held and island. This is no longer the case.

The Mt. Forist House continued to function as a tavern with an additional bid for summer boarders—a popular enterprise in the North Country of yesteryear. When Mr. Forist died, S. F. Leighton and Henry F. Marston then successively conducted the Mt. Forist House for a short time, and then Elizabeth Forist, the wife of Merrill, took charge of the business until February of 1885.The old New England taverns were mostly located on main traveled stagecoach routes. The coming of the railroad took the travel; and the tavern enterprise suffered. It was about this period of Berlin's history where "taverns" became "hotels."

The Tavern got into the hands of Merrill C. Forist, who ran it for several years until it was obtained by Daniel Green, after the foreclosure of a mortgage. In 1874, Sullivan Green with his family returned here from Detroit, Michigan, to "keep house" for his father, Daniel. The tavern was closed as a public house. With business acumen for which she was noted, Mrs.Green, "Aunt Kittie," conducted a popular high-class boarding house until her old age caught up with her. Many families lived here until they could earn enough money to build or buy their own homes.

Now let’s turn our attention back to Merrill C. Forist. In 1866, Mr. Forist purchased a small cottage and made large additions for hotel purposes and opened the Mt. Forist House. It was located on rising groun a little back of the site now occupied by the new Bickford Place park. He continued this hotel until his death in 1879. The accompanying picture was taken from a spot on, what was then called, "the island," directly across the canal in back of Maureen’s boutique. In the photo, one can see the Androscoggin River running in front of the Mt. Forist House, the river once ran where those large green pipes are now (in back of Tony's Pizza), making the little parking lot where the bonfires after the Homecoming pride is held and island. This is no longer the case.

The Mt. Forist House continued to function as a tavern with an additional bid for summer boarders—a popular enterprise in the North Country of yesteryear. When Mr. Forist died, S. F. Leighton and Henry F. Marston then successively conducted the Mt. Forist House for a short time, and then Elizabeth Forist, the wife of Merrill, took charge of the business until February of 1885.The old New England taverns were mostly located on main traveled stagecoach routes. The coming of the railroad took the travel; and the tavern enterprise suffered. It was about this period of Berlin's history where "taverns" became "hotels."

|

In the 1870s, Henry F. Marston came to Berlin from Ellsworth,

Maine, to demonstrate two-sled logging to the local loggers. He ended up staying in Berlin to work for the local mills. He got involved in boarding houses, one such boarding house stood on the corner of Third and Main Street. In 1877, Mr. Marston built a fairly small country house, which he first used for his residence. Shortly after that, he allowed boarders to use it up as a boarding house, that was run by his wife when he was off doing other jobs, and called it the “Whirling Eddy House”. This name came from a formation in the Androscoggin River nearby. It was created by a bend in the bank at that point, forming a large eddy. The Whirling Eddy House, serving as both the boarding house and his own home, became to small, and he was obliged to sleep in the attic. Marston later enlarged this building, renaming it the “Cascade House” (For more information see “St. Regis Academy” on the “Schools” page) In 1888, Mr. Marston purchased land to build a hotel in Green Square. This hotel was called the Berlin House and before this there was just a barn that occupied this lot. With the construction of this new hotel, visitors to the early Berlin could sit on the front porch and watch the early Berlinites shop in the stores and go on with their lives. According to the Lakes and summer resorts in New Hampshire published by the State of New Hampshire in 1892, the Berlin House could hold a maxim of 75 people and charged $2.00 a day, but if you stayed for a week, you would pay $7 -10 dollars. Fifteen years pasted under the ownership of Mr. Marston and in 1903, the Berlin House was sold. After 1903, the Berlin House changed owners frequently and on August 19, 1961, this famous hotel burnt to the ground. The lot where the Berlin House once stood now sits empty next to the Heritage Baptist Church, which is across the street from the Eagle’s Club. |

|

In 1835, Thomas Green Jr., Daniel and Amos Green’s father, built

a building on the site where Tea Birds is today. The building was later bought by John Wilson and used as a house, and also as a boarding house to travelers. One prominent Berlin man was born in this "Wilson House" in 1870, William W. Burlingame by name. William W. Burlingame owned an insurance agency that stood at 83 Main Street. Mr. Burlingame was educated at Burdett College in Boston, later coming back to Berlin and starting one of the largest insurance enterprises north of Concord. He was very involved in sports, and did much to protect local game. He donated his own time and money to make sure local streams were stocked with trout and other fish. He was the city clerk for four years, a library trustee for three years, and, in 1908, was elected to the House of Representatives. Like everything else in this world, these buildings all came to an end. The Berlin Falls House simply was torn down to renew Berlin with bigger and better buildings. The building that replaced this old tavern is called the Rosenfield Block, which was built in 1923, and sits next to the Eagle’s Club. The Mt. Forist House was either torn down or burnt down in the early 1900s. The Wilson House stood in Berlin until the early 1900s also. The Cascade House was eventually bought out by the Catholic Church, and turned into the first building to be called “St. Regis Academy” here in Berlin. It was replaced by the better brick building we have today next to St. Anne’s Church. Perhaps this loss of these buildings was for the best, for we today have very old brick buildings that have a lot of their own history that took place inside of their walls. |