The Hermit of the Swift Diamond River

|

An old man once left the busy city of Berlin, New Hampshire to live a life of peace and solitude in the forest. His last cabin once stood where Four Mile Brook meets the Swift Diamond River. This area was so remote at the time, the fish and game who would often visited him had to wear snowshoes in the winter to get there, unlike today when one can simply take a car there and then walk a short distance and they would be at the spot of his cabin in the matter of seconds. Mr. Erwin Palmer was a millwright and a carpenter living at 772b Second Ave. when he decided to give-up everything to go live in the woods (around 1920). He first built a log cabin on a knoll overlooking Greenough Pond. It is on this spot where he had lived for the first eight years of his new life in the woods. From his first cabin, he could gaze upon both Little and Big Greenough Ponds. He could also sit under a big yellow birch tree and look deep into the state of Maine. Mr. Palmer was nearly, if not completely, self-sufficient, growing fruits and vegetables and hunting for food. He only took what he needed and nothing more. Palmer was eventually forced to move from his first location by the landowners. One can still see the location of Palmer's first cabin today (2014), by looking for a cluster of various fruits that grow in a certain area of the woods by Greenough Pond. |

|

Palmer build his second cabin near where Four Mile Brook empties into the Swift Diamond in the unorganized township of Second College Grant. If one looks on old maps, one can see a location marked as "Palmer's Cabin." This is the location of Palmer's second and last cabin where he lived for six more years. For ten years the New Hampshire Fish and Game often visited him for insights of wildlife activates. They said he was an accurate observer of wildlife, along with having a penetrating and philosophic personality.

One night, Palmer and the fish and game officers sat around a campfire while he described at length the habits of the fisher cat, which is extremely rare in New England. He would observe fishers for hours, and even caught a few, which he sold for $50 dollars and upwards. He also spoke of how he watched a fisher kill a porcupine at his first camp. When the fish and game would visit him, he would devote that whole night to talking about a specific animal and its behaviors, then the next night to another animal and so on.

Wilderness living was nothing new to Palmer. By the time he was in his late teens, he decided that the modern world was too fast pace for him, with its 24 hour radio broadcasts, electric lighting, and telephone communication. He decided that the old-fashioned way of life was for him, with its "it'll get done, when it gets done" type of attitude. He then moved to Alaska, where he traveled with a Native American Indian guide into the deep, unsettled woodlands, hunting, trapping, and prospecting. It's no wonder why he wanted to live like this in our Great North Woods of New Hampshire, this was the only way of life that he knew.

One night, Palmer and the fish and game officers sat around a campfire while he described at length the habits of the fisher cat, which is extremely rare in New England. He would observe fishers for hours, and even caught a few, which he sold for $50 dollars and upwards. He also spoke of how he watched a fisher kill a porcupine at his first camp. When the fish and game would visit him, he would devote that whole night to talking about a specific animal and its behaviors, then the next night to another animal and so on.

Wilderness living was nothing new to Palmer. By the time he was in his late teens, he decided that the modern world was too fast pace for him, with its 24 hour radio broadcasts, electric lighting, and telephone communication. He decided that the old-fashioned way of life was for him, with its "it'll get done, when it gets done" type of attitude. He then moved to Alaska, where he traveled with a Native American Indian guide into the deep, unsettled woodlands, hunting, trapping, and prospecting. It's no wonder why he wanted to live like this in our Great North Woods of New Hampshire, this was the only way of life that he knew.

|

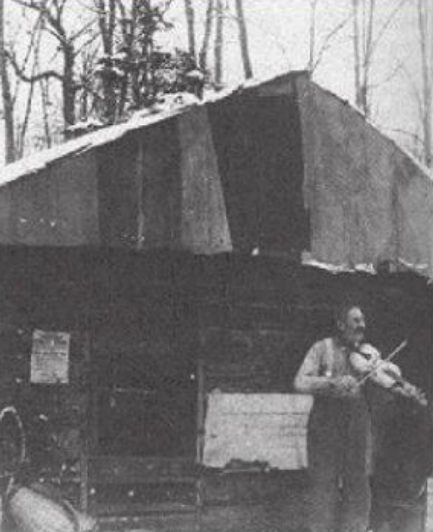

Despite having lots of experiences that the normal human beings don't get to experience, Palmer had no interest in putting his experiences into written form by his own account, but he did want to give something to society so they could remember him. He decided that he was going to make a violin that could only be compared to those of Stradivarius and other matchless makes that had been created in the past. He figured that society has accomplished so much since his childhood but no one has yet to make a violin that could match the sound of the Italian great works. Although Palmer had never played the violin before, nor did he have a photo or a diagram of how one is build, he decided that he would make one since he had found the butt end of an old bird's eye maple log.

He went to a friend's house in Errol, where he took a look at a violin. He then wrote to Boston and received a picture of one. He then began work on his violin with this limited information. He spent many years working by himself at his little work bench that he had built at his second camp. He worked during the night in the winter months; his cabin being lit by an old, beat-up kerosene lamp. Palmer's story is one of extraordinary persistence and endurance. Take a moment to imagine how long and hard this man had to work to make these violins! Most people would have just given up, but that wasn't Palmer's personality. Although he was a believer in the "It'll get done, when it gets done" type of attitude, he was not a lazy man. After all, when you slow down and take your time to do things, you get a better quality product. Palmer made every piece of the violin by hand, except the strings. |

After he made his first violin and began playing it, he noticed the glue that he had made himself was not strong enough. The problem was that when the violin was played, it vibrated and caused it to come apart. One day two sportsmen stumbled upon Palmer's cabin while out hunting and what not. One of the men was in the automobile manufacturing business in Detroit, and the other was a surgeon from New York City. They all drank some tea that Palmer had made for them and he discussed the problems that he had with the construction of his violin.

They assured him that they would help him out and went on their way. Quite some time after the men had left the cabin, Palmer received some strong glue that was used in car manufacturing from the Detroit man, and later the man from New York sent him a genuine Amati violin with a letter telling him that he should take it apart to see how it was made. The odd thing about this is that Palmer never took apart the Amati violin, but he did use the glue and was very satisfied by it. Palmer made seven violins while he was at his second cabin, and as before said, all were handmade except for the string. One violin was sold for $500 dollars, another was stolen, and yet another was damaged in some way or another.

With all the people who passed by Palmer's cabin in the "Swift Diamond Country" of New Hampshire, only one was a expert violin player. When the expert did play "Palmer's Masterpiece" there was only Palmer and himself in a remote cabin in the wilderness, far form where the great violins that he was trying to equal are played. Palmer was forced to leave his cabin due to illness and was taken to West Stewartstown, where he passed away in 1934. He was a hermit that lived near the Swift Diamond River in New Hampshire for 14 years, 12 years longer than Henry Thoreau did at Walden Pond in Massachusetts. Maybe someday one of Erwin J. Palmer's masterpiece violins will turn up with the passage of time with all the glorious beauty and plangent melody of a genuine Amati.

They assured him that they would help him out and went on their way. Quite some time after the men had left the cabin, Palmer received some strong glue that was used in car manufacturing from the Detroit man, and later the man from New York sent him a genuine Amati violin with a letter telling him that he should take it apart to see how it was made. The odd thing about this is that Palmer never took apart the Amati violin, but he did use the glue and was very satisfied by it. Palmer made seven violins while he was at his second cabin, and as before said, all were handmade except for the string. One violin was sold for $500 dollars, another was stolen, and yet another was damaged in some way or another.

With all the people who passed by Palmer's cabin in the "Swift Diamond Country" of New Hampshire, only one was a expert violin player. When the expert did play "Palmer's Masterpiece" there was only Palmer and himself in a remote cabin in the wilderness, far form where the great violins that he was trying to equal are played. Palmer was forced to leave his cabin due to illness and was taken to West Stewartstown, where he passed away in 1934. He was a hermit that lived near the Swift Diamond River in New Hampshire for 14 years, 12 years longer than Henry Thoreau did at Walden Pond in Massachusetts. Maybe someday one of Erwin J. Palmer's masterpiece violins will turn up with the passage of time with all the glorious beauty and plangent melody of a genuine Amati.