Berlin Falls

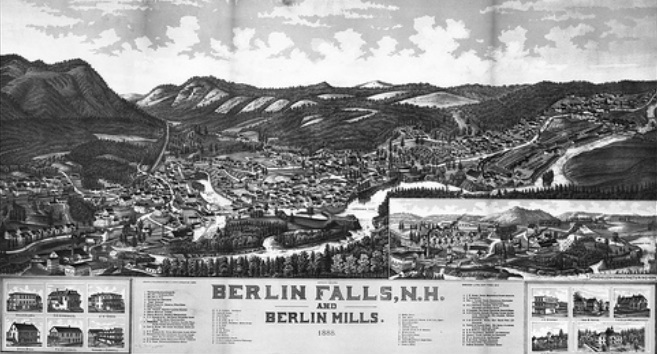

Berlin Falls village in 1888

If there were no other attraction in the Gorham Valley, part of a day, at least, out of the mountain journey, should be devoted to the village for the sake of the drive to this, the most powerful cataract of the mountain region. Cascades we can see in other districts of the hills. The Ammonoosuc Falls are very powerful after a heavy rain, though the turbine of their flood gives them little beauty then. But here we have a strong river that shrinks but very little in long droughts, and that is fed by the Umbagog chain of lakes, pouring a clean and powerful tide through a narrow granite pass, and descending nearly two hundred feet in the course of a mile.

The ride to the Berlin Falls is charming. The road is on the western bank of the Androscoggin all the way. The river moves now and then in such sweeping curves, and is overhung for most of the distance by a mountain with foliage so massive and varied, and the gradual descent of the river-bed gives the current, during a great portion of the way, so much briskness, while the mountain views behind are so majestic, that the six miles, if we drive in an open wagon, do not seem long enough, however eager we may have been to see the cataract. There is no hard climbing or long walking required, after leaving the vehicle.

The Falls are close by the road. It is a winding granite gorge through which the river rushes, over the narrowest part of which a stout bridge is thrown. Visitors should alight at the lowest part of the cataract, and go out through a little thicket of trees upon a mossy ledge, about fifteen feet above the current, where they can face the sweeping torrent. How madly it hurls the deep transparent amber down the pass and over the boulders,—flying and roaring like a drove of young lions, crowding each other in furious rush after prey in sight. On the bridge, we look down and see the current shooting swifter than the "arrowy Rhone," and overlapped on either side by the hissing foam thrown back from each of the rock walls. Above the bridge, we can walk on the ledge of the right-hand bank, and sit down where we can touch the water and see the most powerful plunge of all, where half of the river leaps in a smooth cataract, and, around a large rock which, though sunken, seems to divide the motion of the flood, a narrow and tremendous current of foam shoots into the pass, and mingles its fury at once with the burden of the heavier fall.

We do not think that in New England there is any passage of river passion that will compare with the Berlin Falls. But if we stay long on the borders of the gorge, as we ought to, we shall find that the form and the rage of the current are subordinate in interest to its beauty and to the general surrounding charm. Who can tire of gazing at the amber flood, from the point first described, to see the white frostwork start out over its whole breadth, and renew itself as fast as it dies? Fix the eye upon the centre of that flood, and it Beems to be a flying sheet of golden satin, with silver brocade leaping out to overshoot it, as it hurries from its loom. An artist, with whom more than once we have rested on the bank to catch the short-lived effects on the shifting currents of the river, speaks of the charm of "the foam foliage, white and prismatic, that crests the leaping waves, running from fall to fall, and circling dark domes of water that revolve over submerged stones." He recalls the grace of “the fountain jets of silver spray, and of the ever-falling crystal fringes that hang around the black rocks." And he tells us that, at such a spot, "by joining somewhat of the poet's contemplation to the artist's study, we may see glimpses of sylphic shapes, shining in the darkness of some thin-curtained arch, or, glancing along the liquid coils from pool to pool, nimbly working out those rapidly changing designs, whose wondrous beauty and inexhaustible variety are not inherent in material things, but are possible only to fairy or supernatural powers."

The sides of the rocks through which the Androscoggin thus pours are charmingly colored with lichens and weather-stains. In the crannies and little juttings on the sides where soil has lodged, grasses, small bushes, and wild flowers have taken root, and unfold their verdure and beauty undisturbed by the wrath below. Out to the very edge of the walls, young birches and pines, too, have stationed themselves to catch the fresh mists that rise. It was a cataract in Switzerland for which Wordsworth wrote the following sonnet; but how could it be more appropriate if it had been written as a description of the torrent in whose praise we quote it? What more can we say than that its fitness is equal to its beauty?

"From the fierce aspect of this River, throwing

His giant body o'er the steep rock's brink,

Back in astonishment and fear we shrink:

But, gradually a calmer look bestowing,

Flowers we espy beside the torrent growing;

Flowers that peep forth from many a cleft and chink,

And, from the whirlwind of his anger, drink

Hues ever fresh, in rocky fortress blowing:

They suck—from breath that, threatening to destroy,

Is more benignant than the dewy eve--

Beauty, and life, and motions as of joy:

Nor doubt but He to whom yon Pine-trees nod

Their heads in sign of worship, Nature's God,

These humbler adorations will receive."

Those who have passed a delightful hour or two of the afternoon by Berlin Falls, and who read these pages, will be tempted to ask us, as we now turn from them, " Why do you not say something of the inspiring view of Mounts Madison and Adams, whose peaks, seen from the bridge, soar with such proud strength in the western sky? Why do you not call attention to the glorious lines that support their crests,—those of Madison a little more feminine than those of Adams, but both majestic,—a lioness and lion crouched side by side, half resting, half watching, with muscles ready in a moment for vigorous use? Why do you not try to report the singular charm of looking down the broad stream, roughened with foamy rapids, as it hurries towards the base of those twin crests, and of the rich colors that combine in the harmony of, the picture,—the snowy caps on the blue river, the green banks, the gray and gold of the mountain slopes and crowns?" We certainly would not overlook these features of the landscape at Berlin Falls; but we have a richer pleasure in store for our readers by inviting them to take with us.

The ride to the Berlin Falls is charming. The road is on the western bank of the Androscoggin all the way. The river moves now and then in such sweeping curves, and is overhung for most of the distance by a mountain with foliage so massive and varied, and the gradual descent of the river-bed gives the current, during a great portion of the way, so much briskness, while the mountain views behind are so majestic, that the six miles, if we drive in an open wagon, do not seem long enough, however eager we may have been to see the cataract. There is no hard climbing or long walking required, after leaving the vehicle.

The Falls are close by the road. It is a winding granite gorge through which the river rushes, over the narrowest part of which a stout bridge is thrown. Visitors should alight at the lowest part of the cataract, and go out through a little thicket of trees upon a mossy ledge, about fifteen feet above the current, where they can face the sweeping torrent. How madly it hurls the deep transparent amber down the pass and over the boulders,—flying and roaring like a drove of young lions, crowding each other in furious rush after prey in sight. On the bridge, we look down and see the current shooting swifter than the "arrowy Rhone," and overlapped on either side by the hissing foam thrown back from each of the rock walls. Above the bridge, we can walk on the ledge of the right-hand bank, and sit down where we can touch the water and see the most powerful plunge of all, where half of the river leaps in a smooth cataract, and, around a large rock which, though sunken, seems to divide the motion of the flood, a narrow and tremendous current of foam shoots into the pass, and mingles its fury at once with the burden of the heavier fall.

We do not think that in New England there is any passage of river passion that will compare with the Berlin Falls. But if we stay long on the borders of the gorge, as we ought to, we shall find that the form and the rage of the current are subordinate in interest to its beauty and to the general surrounding charm. Who can tire of gazing at the amber flood, from the point first described, to see the white frostwork start out over its whole breadth, and renew itself as fast as it dies? Fix the eye upon the centre of that flood, and it Beems to be a flying sheet of golden satin, with silver brocade leaping out to overshoot it, as it hurries from its loom. An artist, with whom more than once we have rested on the bank to catch the short-lived effects on the shifting currents of the river, speaks of the charm of "the foam foliage, white and prismatic, that crests the leaping waves, running from fall to fall, and circling dark domes of water that revolve over submerged stones." He recalls the grace of “the fountain jets of silver spray, and of the ever-falling crystal fringes that hang around the black rocks." And he tells us that, at such a spot, "by joining somewhat of the poet's contemplation to the artist's study, we may see glimpses of sylphic shapes, shining in the darkness of some thin-curtained arch, or, glancing along the liquid coils from pool to pool, nimbly working out those rapidly changing designs, whose wondrous beauty and inexhaustible variety are not inherent in material things, but are possible only to fairy or supernatural powers."

The sides of the rocks through which the Androscoggin thus pours are charmingly colored with lichens and weather-stains. In the crannies and little juttings on the sides where soil has lodged, grasses, small bushes, and wild flowers have taken root, and unfold their verdure and beauty undisturbed by the wrath below. Out to the very edge of the walls, young birches and pines, too, have stationed themselves to catch the fresh mists that rise. It was a cataract in Switzerland for which Wordsworth wrote the following sonnet; but how could it be more appropriate if it had been written as a description of the torrent in whose praise we quote it? What more can we say than that its fitness is equal to its beauty?

"From the fierce aspect of this River, throwing

His giant body o'er the steep rock's brink,

Back in astonishment and fear we shrink:

But, gradually a calmer look bestowing,

Flowers we espy beside the torrent growing;

Flowers that peep forth from many a cleft and chink,

And, from the whirlwind of his anger, drink

Hues ever fresh, in rocky fortress blowing:

They suck—from breath that, threatening to destroy,

Is more benignant than the dewy eve--

Beauty, and life, and motions as of joy:

Nor doubt but He to whom yon Pine-trees nod

Their heads in sign of worship, Nature's God,

These humbler adorations will receive."

Those who have passed a delightful hour or two of the afternoon by Berlin Falls, and who read these pages, will be tempted to ask us, as we now turn from them, " Why do you not say something of the inspiring view of Mounts Madison and Adams, whose peaks, seen from the bridge, soar with such proud strength in the western sky? Why do you not call attention to the glorious lines that support their crests,—those of Madison a little more feminine than those of Adams, but both majestic,—a lioness and lion crouched side by side, half resting, half watching, with muscles ready in a moment for vigorous use? Why do you not try to report the singular charm of looking down the broad stream, roughened with foamy rapids, as it hurries towards the base of those twin crests, and of the rich colors that combine in the harmony of, the picture,—the snowy caps on the blue river, the green banks, the gray and gold of the mountain slopes and crowns?" We certainly would not overlook these features of the landscape at Berlin Falls; but we have a richer pleasure in store for our readers by inviting them to take with us.

A Drive to Milan

Abbott House in Milan, 1862

It disturbs our geographical prejudices a little, perhaps, to be told that only six or seven miles divide settlements with such distinguished names. But it will help us to discriminate if we learn to pronounce these names as the Yankees do$ with the accent strong on the first syllable. We should look in vain for any imperial palace as we drive through our Berlin; and instead of a university we shall see only a cluster of saw-mills, where part of the forests of Umbagog are prepared for service to civilization. So too, if we should ride to the very borders of Milan, we might not find- in the red spire of the village church that would greet us, the artistic satisfaction which one would anticipate from the first glimpse of the Duomo, which we associate with the capital of Lombardy. (A wicked friend of ours who took the drive with us, when the village first saluted our eyes remarked, that this Milan seemed to be set in the plain of Lumber-dy.)

But we will not drive so far as the village. We will "follow the road" about two miles above Berlin Falls, cross the large, covered bridge of the Androscoggin, and drive about two miles above that on the eastern bank of the river. Then we will turn the horses' heads again towards Gorham. Now look down the river towards the mountains! Do we see the two peaks that were so fascinating at the Falls below? They have received an addition to their company. There are three now. Mount Washington has lifted his head into sight behind Madison, and has pushed out the long outline of the ridge that climbs from the Pinkham forest, and by all the stairways of his plateaus, to his cold and rugged crown. What a majestic trio! What breadth and mass, and yet what nervous contours! The mountains are arranged in half circle, so that we see each summit perfectly defined, and have the outline of each on its character

istic side lying sharp against the sky,—Adams as it is braced from the north, Madison from the southeast, Washington from the south. They hide the other summits of the range completely. And from our position we look down the long avenue of hills that guard the Androscoggin, and over the wilderness from which they spring, and see them from a height very favorable for revealing their elevation, and through a sufficient depth of air to give them both distinctness and bloom.

Is it not something to mourn over, that the spectacle of this bivouac of hills should have been so seldom seen by tourists in New Hampshire? Many thousands visit the White Mountains in the summer weeks, and not fifty have as yet looked upon this landscape, so easily attained by a drive of an hour and a half from the hotel in Gorham. Up to the time of our writing these pages, more' people in England have enjoyed this view through a painting of it by the artist whose sketch is here presented to our readers, and who sent it abroad in answer to an order, than in our own country have seen the Creator's original. We shall be glad if anything in this unworthy description proves a temptation to future visitors of the eastern valley of the mountains to take this drive towards Milan in a clear afternoon, and thus add such a powerful combination of the mountain forms, dimpled and flushed too with countless shadows and tints, to the treasures of their memory.

It is worth while to take the additional few miles of ride above Berlin Falls to the point where we are now resting, in order to see the river so calm. On a still afternoon it sleeps here as though it had not been troubled above, and had no more hard fortune to encounter below. This level passage in its history, where it coaxes the grasses and trees of its shores down into its silence, as the water spirit of Goethe's ballad seduced the Fisher into the stream, is kindred with the quiet of the English river, above its cataract, which Wordsworth thus describes :--

"The old inventive Poets, had they seen,

Or rather felt, the entrancement that detains

Thy waters, Duddon! 'mid these flowery plains;

The still repose, the liquid lapse serene,

Transferred to bowers imperishably green,

Had beautified Elysium! But the chains

Will soon be broken;—a rough course remains,

Rough as the past; where Thou, of placid mien,

Innocuous as a firstling of the flock,

And countenanced like a soft cerulean sky,

Shalt change thy temper; and with many a shock

Given and received in mutual jeopardy,

Dance, like a Bacchanal, from rock to rock,

Tossing her frantic thyrsus wide and high!"

But our readers, whom we have specially invited as guests on this excursion, must not be kept out after dark. We shall have the late hours of the afternoon for a slow drive down to Gorham, and a short call again upon the falls in Berlin on the way. Of course our readers all know that about six in the evening of a midsummer day is the time for a drive. From five to half-past seven is worth all the rest of the day. Nature, as Willis has charmingly said, pours the wine of her beauty twice a day,—in the early morning, and evening, when the long shadows fall. In the mountain region the saying is more strictly true,—not only as to shadows, but in regard to colors. Her richest flasks are reserved for the dessert-hour of the day's feast. Then they are bountifully poured.

"Then flows amain

The surge of summer's beauty; dell and crag,

Hollow and lake, hill-side, and pine arcade,

Are touched with genius."

Yes indeed, it is the wine of beauty that is poured out around the valley now. Who can give the key to that magic of the evening sun by which he sheds over the hills the most various juices of light from his single urn? Those substantial twin majesties, Madison and Adams, have a steady preference for the brown-sherry hues,—though round their bases they are touched with an azure that is held in dark sapphires, but never was caught by any wine. The Androscoggin hills take to the lighter and brilliant yellows, the hocks and champagne; the clarets, the Red Hermitage, the purple Burgundies, seem to be monopolized by the ridge of Mount Carter and Mount Moriah.

Would that it could be our fortune to see on the Mount Moriah range, before we reach the hotel, a counterfeit such as we once saw at sunset, of the majesty and splendor of Mont Blanc at evening! The clouds piled themselves over the long range as if they were organized into the mountain,—as if they were ridges and pinnacles draped with snow. Back of them lay a sky perfectly clear, but not blue; it was green,—such green as you see in the loop of a billow about to break in foam on a shelving, rocky shore. The west was drenched in peach bloom; and over the whole mass of the towering fleece that mimicked Mont Blanc, was spread a golden flush just ready to flicker into rose-color, that was as glorious as any baptism of splendor upon Chamouni; and which faded away to leave a death pallor as mournful as the up heaved snows of Switzerland can show, after the soul of sunshine has mounted from their crests.

And let us have the privilege of describing what we cannot hope to see again, a spectacle upon one portion of the Mount Moriah range, which has made one return ride to Gorham, from Berlin Falls, an enduring pleasure. Thus we wrote of it at the time :--

"The vapora hung in heavy masses over the principal ridges, but the west was clear. There was evident preparation for a magnificent display,—a great banquet by the sun to the courtier clouds, on retiring from office that day,—a high carnival of light. As I turned the horse towards Gorham, taking the Moriah range full in view, a slight shower began to fall down the valley of Mount Carter and a patch of rainbow flashed across the bosom of the mountain. From point to point it wandered, uncertain where to 'locate,' but at last selected a central spot against the lowest summit, and concentrated its splendors.

The background of the mountain was blue-black. Not a tree was visible, not an irregularity of the surface. It was one smooth mass of solid darkness, soft as it was deep. And the iris was not a bow, but a pillar of light. It rested on the ground; its top did not quite reach to the summit of the mountain. With what intense delight we looked at it., expecting every instant that its magic texture would dissolve! But it remained and glowed more brightly. I can give you no conception of the brilliancy and delicacy, the splendor and softness, of the vision. The rainbow on a cloud, in the most vivid display I ever saw of it, was pale to this blazing column of untwisted light. The red predominated. Its intensity increased till the mountain shadow behind it was black as midnight. And yet the pillar stood firm. 'Is not the mountain on fire?' said my companion. 'Certainly that is flame.' Five minutes, ten minutes, fifteen minutes, the gorgeous vision staid, and we steadily rode nearer. Really we began to feel uneasy. We expected to see smoke. The color was so intense that there seemed to be real danger of the trees kindling under it. We could not keep in mind that it was celestial fire we were looking at,—fire cool as the water-drops out of which it was born, and on which it reclined. It lay apparently upon the trees, diffused itself among them, from the valley to the crown of the ridge, as gently as the glory in the bush upon Horeb, when 'the angel of the Lord appeared unto Moses in a flame of fire, out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and behold the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed.

It seemed like nothing less than a message to mortals from the internal sphere,—the robes of an angel, awful and gentle, come to bear a great truth to the dwellers in the valley. And it was, no doubt. It meant all that the discerning eye and reverent mind felt it to mean. That Arabian bush would have been vital with no such presence, perhaps, to the gaze of a different soul. 'To him that hath shall be given.' A colder, a skeptical spirit would have said, possibly, 'there is a curious play of the sunbeams in the mist about that shrub,' or, it may be, would have decided that he was the victim of an optical illusion, and so would have missed the message to put the shoes from his feet, because the place was holy ground. Nearly twenty minutes the pillar of variegated flame remained in the valley of Mount Carter, as if waiting for some spectator to ask its purpose, and listen for a voice to issue from its mystery. Then, lifting itself from its base, and melting gradually upwards, it shrunk into a narrow Btrip of beauty, leaped from the mountain summit to the cloud, and vanished.

It seems difficult to connect such a show, in memory, with 'Gorham,'—so hard a name, a fit title for a rough, growing Yankee village. But such is the way the homeliest business is glorified here; such is the way the ideal world plays out visibly over the practical, in all seasons, and every day. Only have an eye in your head competent to appreciate the changes of light, the richness of shadows, the sport of mists upon the hills, and you can look up every hour, here, from the rough fences and uncouth shops of Yankee land, to the magic of fairy land. While that show was in the height of its splendor, I asked an old farmer, who was hauling stones with his oxen, what he thought of it. He turned, snatched the scene with his eye, and said indifferently, 'It's nice, but we often have 'em here; gee-haw, woo-hush!' Yes, that's just the truth. 'We often have 'em,'--often have the glories of the Divine art, passages of the celestial magnificence, playing over our potato fields; therefore the us pay no attention to them,—count them as matters of course, keep coolly at our digging, and wait for something more surprising to jar us from our skepticism, shatter the crusts of the senses, wake us to a feeling of mystery, and startle us, through fear, into a belief or consciousness of God.

The iris-pillar suggested the burning bush on Horeb. As I close this letter, that passage broadens to my thought, into a symbol of a mightier truth. What statement is so competent as that to set forth the relation of the Creative Spirit to the universe? In Moses' time, nature, in the regard of science, was a mere bush, a single shrub. Now it has grown, through the researches of the intellect, to a tree. The universe is a mighty tree; and the great truth for us to connect with the majestic science of these days, and to keep vivid by a religious imagination, is, that from the roots of its mystery to the silver leaved boughs of the firmament, it is continually filled with God, and yet unconsumed."

At the commencement of this chapter we alluded to the beauty of the drive from Bethel to the hotel in Gorham. One of the prominent resources of a visitor who stays a week or two at the Alpine House, is a ride of ten or twelve miles down the Androscoggin on its right-hand bank, through Shelburne to Gilead, and then up the river on the easterly bank, crossing it again at Lead-Mine bridge. This drive can be taken before sunset on a long summer day, by leaving the Alpine House just after dinner. And no drive of equal length among the mountains offers more varied interest in the beauty of the scenery, the historic and traditional associations involved with the prominent points of the landscape, and the scientific attractions connected with some portions of the road.

In Shelburne, a small village six miles below Gorham, the driver will point out the remains of a boulder, which, before it was blown for use on the railroad track, overhung a ledge that has received the name of " Granny Star bird," or as it is sometimes spelled, " Granny Stalbird." She was the first woman who climbed through the great White Mountain Notch, from Bartlett,—a feat which she accomplished in 1776, on her way to Dartmouth (now Jefferson) to serve in the family of Col. Whipple. Many years afterwards, when a widow, she became very skilful as a doctresses, and often travelled great distances on horseback to visit the scattered settlers in their sickness. When she was very old, she was sent for to visit a sick person below Shelburne, but was overtaken in the night by a tremendous thunderstorm. The rain and wind were so furious that it was impossible for her to keep the road against it, and she drove her horse under the boulder that overhung this ledge, and stood by him, holding the bridle, all night. The wind howled frightfully around her, and the lightning showed her rivulets tearing across the road to swell the Androscoggin; but the hardy old heroine faced it without dismay, and did not leave the rude shelter until noon of the next day, when the storm abated. The builders of the Grand Trunk Railway through Shelburne ought to be indicted for blasting that rock, which belonged to the poetry of the mountains, when any common granite of the neighborhood could as easily have served their prosaic needs.

The history of Shelburne, as of Bartlett and Bethlehem, startles us with the records of suffering which the pioneers in the mountain valleys were willing to undergo in establishing homes there. In 1781, a man, with a wife and three children, moved into Shelburne when the snow was five feet deep on the ground, and the Androscoggin was a bed of ice. The mother carried the youngest child, nine months old, in her arms; a boy of four and a girl of six trudged by her side. Their shelter was a wretched cabin with just enough rough shingles laid across some poles on the top, to cover a space large enough for a bed. Their cow was provided with a large square hole in the snow covered with poles and boughs.

The stories of the ravages of bears and wolves in the neighborhood of Shelburne are more striking than those recorded of any other portions of the mountains. On the drive from Gorham to Gilead, the wagon passes a portion of the road where a pack of wolves attacked an Indian, and killed and devoured him, but not till they had lost seven of their starving band in the encounter; and to their other afflictions, the early settlers of this neighborhood were troubled, as those in the Bartlett Valley were not, by Indian invasions. They experienced not only the hardships of isolation and cold, and the plunder of wild beasts, and the ravage of mountain torrents, and the desolation of freshets, but they knew the terror of the war-whoop, and some of their number felt the scalping-knife and tomahawk, as well as the horrors of Indian captivity. The last of the outrages by the savage tribes in New Hampshire broke upon the settlements along the Androscoggin above Bethel. In August of 1781 a band of Indians made an attack upon Bethel, and after plundering some of the settlers, and taking others with them as captives, came up through Gilead, murdered one of the hardy settlers there, robbed the cabin of the family that had moved into Shelburne on the snow, and carried their prisoners by Umbagog Lake into Canada. When the pooi captives were so worn down with the march through the wilderness, and the loads which the savages laid upon them, that they were ready to faint with fatigue and hunger, the brutes would broil old moccasins of moose skin, tainted by the heat, for their food. One of the party who escaped describes the hideousness of a war-dance in which the Indians disported themselves, in one of the rocky passes through which they were taken. He says, “It almost made our hair stand upright upon our heads. It would seem that Bedlam had broken loose, and that hell was in an uproar." During one of the carousals the Indians amused themselves with throwing firebrands at a Negro called Black Plato, whom they set up as a mark. The man who gives us this account returned to the old neighborhood on the Androscoggin, and lived many years to tell of the hardships of the first settlers, and to see pleasant villages and fruitful fields adorn and enrich a large portion of the valley, through which he and his party were hurried in 1781.

And yet no Indian tragedy is so frightful as the civilized one which is connected with Gilead below Shelburne, and whose date is as recent as June, 1850. Here a Mr. Freeman lived, with a young and beautiful wife and three children. He was a blacksmith, and was employed in the service of the company that were building the railroad from Portland to Montreal. A contractor on the railroad boarded in his family. This man succeeded in alienating the affection of the young wife from her husband, and soon after left the village for New York. The young husband, who was passionately devoted to his wife, found very soon that she had lost all interest in him and in her children. At last, after insisting on a divorce, to which he would not listen, she told him that she should leave his house, and commenced preparations for a journey. A trunk arrived, which Mr. Freeman intercepted, in which he found beautiful dresses and jewelry for his wife, and a letter from the contractor making an appointment to meet her in Syracuse in New York. Mrs. Freeman did not learn of the arrival of the trunk or letter. But she still insisted on leaving her husband, and even informed him on what day she should depart. On the night previous the young husband sat up very long in conversation with his wife, and after she went to her chamber, he left the house. But who is that peering into the window when the light is out, and all is still? About midnight, the piercing shriek rose from her room, " I am murdered!" She was found with her arm shattered, and her head wounded by a charge of buckshot, that had been fired through the window from a musket which had evidently been aimed with care at her heart. "It was my husband," she said to those that gathered in the room. "And will he not come? Oh, George, my dear husband, shall I not see him to be forgiven?" She died before dawn, without any reproaches for her murderer, and with his name on her lips. Many hours after, the husband was found dead, about a mile from his house, and in his hand the fatal razor that had relieved his agony. The tragedy was deliberately planned; for in his house were found letters that contained directions in regard to his children, and the disposition of his property.

Let us drive now across the river, with the horses' heads towards Gorham again, and make our first halt near the house of Mr. Gates in Shelburne, under the shadow of Baldcap Mountain. If we had time to speak of the view from the summit, which requires about two hours' climbing, we should need words more rich than would come at our bidding. But how grand and complete is the landscape that stretches before us as we look up the river seven or eight miles to the base of Madison and to the bulk of Washington, whose majestic dome rises over two curving walls of rock, that are set beneath it like wings! Seen in the afternoon light, the Androscoggin and its meadows look more lovely than on any portion of the road between Bethel and Gorham, and more fascinating than any piece of river scenery it has ever been our fortune to look upon in the mountain region. The rock and cascade pictures in the forests of Baldcap well reward the rambles of an hour or two. Boarders for the summer, at moderate price, have been taken at Mr. Gates's, and we do not know of any farm-house where the view from the door offers so many elements of a landscape that can never tire.

But we will not drive so far as the village. We will "follow the road" about two miles above Berlin Falls, cross the large, covered bridge of the Androscoggin, and drive about two miles above that on the eastern bank of the river. Then we will turn the horses' heads again towards Gorham. Now look down the river towards the mountains! Do we see the two peaks that were so fascinating at the Falls below? They have received an addition to their company. There are three now. Mount Washington has lifted his head into sight behind Madison, and has pushed out the long outline of the ridge that climbs from the Pinkham forest, and by all the stairways of his plateaus, to his cold and rugged crown. What a majestic trio! What breadth and mass, and yet what nervous contours! The mountains are arranged in half circle, so that we see each summit perfectly defined, and have the outline of each on its character

istic side lying sharp against the sky,—Adams as it is braced from the north, Madison from the southeast, Washington from the south. They hide the other summits of the range completely. And from our position we look down the long avenue of hills that guard the Androscoggin, and over the wilderness from which they spring, and see them from a height very favorable for revealing their elevation, and through a sufficient depth of air to give them both distinctness and bloom.

Is it not something to mourn over, that the spectacle of this bivouac of hills should have been so seldom seen by tourists in New Hampshire? Many thousands visit the White Mountains in the summer weeks, and not fifty have as yet looked upon this landscape, so easily attained by a drive of an hour and a half from the hotel in Gorham. Up to the time of our writing these pages, more' people in England have enjoyed this view through a painting of it by the artist whose sketch is here presented to our readers, and who sent it abroad in answer to an order, than in our own country have seen the Creator's original. We shall be glad if anything in this unworthy description proves a temptation to future visitors of the eastern valley of the mountains to take this drive towards Milan in a clear afternoon, and thus add such a powerful combination of the mountain forms, dimpled and flushed too with countless shadows and tints, to the treasures of their memory.

It is worth while to take the additional few miles of ride above Berlin Falls to the point where we are now resting, in order to see the river so calm. On a still afternoon it sleeps here as though it had not been troubled above, and had no more hard fortune to encounter below. This level passage in its history, where it coaxes the grasses and trees of its shores down into its silence, as the water spirit of Goethe's ballad seduced the Fisher into the stream, is kindred with the quiet of the English river, above its cataract, which Wordsworth thus describes :--

"The old inventive Poets, had they seen,

Or rather felt, the entrancement that detains

Thy waters, Duddon! 'mid these flowery plains;

The still repose, the liquid lapse serene,

Transferred to bowers imperishably green,

Had beautified Elysium! But the chains

Will soon be broken;—a rough course remains,

Rough as the past; where Thou, of placid mien,

Innocuous as a firstling of the flock,

And countenanced like a soft cerulean sky,

Shalt change thy temper; and with many a shock

Given and received in mutual jeopardy,

Dance, like a Bacchanal, from rock to rock,

Tossing her frantic thyrsus wide and high!"

But our readers, whom we have specially invited as guests on this excursion, must not be kept out after dark. We shall have the late hours of the afternoon for a slow drive down to Gorham, and a short call again upon the falls in Berlin on the way. Of course our readers all know that about six in the evening of a midsummer day is the time for a drive. From five to half-past seven is worth all the rest of the day. Nature, as Willis has charmingly said, pours the wine of her beauty twice a day,—in the early morning, and evening, when the long shadows fall. In the mountain region the saying is more strictly true,—not only as to shadows, but in regard to colors. Her richest flasks are reserved for the dessert-hour of the day's feast. Then they are bountifully poured.

"Then flows amain

The surge of summer's beauty; dell and crag,

Hollow and lake, hill-side, and pine arcade,

Are touched with genius."

Yes indeed, it is the wine of beauty that is poured out around the valley now. Who can give the key to that magic of the evening sun by which he sheds over the hills the most various juices of light from his single urn? Those substantial twin majesties, Madison and Adams, have a steady preference for the brown-sherry hues,—though round their bases they are touched with an azure that is held in dark sapphires, but never was caught by any wine. The Androscoggin hills take to the lighter and brilliant yellows, the hocks and champagne; the clarets, the Red Hermitage, the purple Burgundies, seem to be monopolized by the ridge of Mount Carter and Mount Moriah.

Would that it could be our fortune to see on the Mount Moriah range, before we reach the hotel, a counterfeit such as we once saw at sunset, of the majesty and splendor of Mont Blanc at evening! The clouds piled themselves over the long range as if they were organized into the mountain,—as if they were ridges and pinnacles draped with snow. Back of them lay a sky perfectly clear, but not blue; it was green,—such green as you see in the loop of a billow about to break in foam on a shelving, rocky shore. The west was drenched in peach bloom; and over the whole mass of the towering fleece that mimicked Mont Blanc, was spread a golden flush just ready to flicker into rose-color, that was as glorious as any baptism of splendor upon Chamouni; and which faded away to leave a death pallor as mournful as the up heaved snows of Switzerland can show, after the soul of sunshine has mounted from their crests.

And let us have the privilege of describing what we cannot hope to see again, a spectacle upon one portion of the Mount Moriah range, which has made one return ride to Gorham, from Berlin Falls, an enduring pleasure. Thus we wrote of it at the time :--

"The vapora hung in heavy masses over the principal ridges, but the west was clear. There was evident preparation for a magnificent display,—a great banquet by the sun to the courtier clouds, on retiring from office that day,—a high carnival of light. As I turned the horse towards Gorham, taking the Moriah range full in view, a slight shower began to fall down the valley of Mount Carter and a patch of rainbow flashed across the bosom of the mountain. From point to point it wandered, uncertain where to 'locate,' but at last selected a central spot against the lowest summit, and concentrated its splendors.

The background of the mountain was blue-black. Not a tree was visible, not an irregularity of the surface. It was one smooth mass of solid darkness, soft as it was deep. And the iris was not a bow, but a pillar of light. It rested on the ground; its top did not quite reach to the summit of the mountain. With what intense delight we looked at it., expecting every instant that its magic texture would dissolve! But it remained and glowed more brightly. I can give you no conception of the brilliancy and delicacy, the splendor and softness, of the vision. The rainbow on a cloud, in the most vivid display I ever saw of it, was pale to this blazing column of untwisted light. The red predominated. Its intensity increased till the mountain shadow behind it was black as midnight. And yet the pillar stood firm. 'Is not the mountain on fire?' said my companion. 'Certainly that is flame.' Five minutes, ten minutes, fifteen minutes, the gorgeous vision staid, and we steadily rode nearer. Really we began to feel uneasy. We expected to see smoke. The color was so intense that there seemed to be real danger of the trees kindling under it. We could not keep in mind that it was celestial fire we were looking at,—fire cool as the water-drops out of which it was born, and on which it reclined. It lay apparently upon the trees, diffused itself among them, from the valley to the crown of the ridge, as gently as the glory in the bush upon Horeb, when 'the angel of the Lord appeared unto Moses in a flame of fire, out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and behold the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed.

It seemed like nothing less than a message to mortals from the internal sphere,—the robes of an angel, awful and gentle, come to bear a great truth to the dwellers in the valley. And it was, no doubt. It meant all that the discerning eye and reverent mind felt it to mean. That Arabian bush would have been vital with no such presence, perhaps, to the gaze of a different soul. 'To him that hath shall be given.' A colder, a skeptical spirit would have said, possibly, 'there is a curious play of the sunbeams in the mist about that shrub,' or, it may be, would have decided that he was the victim of an optical illusion, and so would have missed the message to put the shoes from his feet, because the place was holy ground. Nearly twenty minutes the pillar of variegated flame remained in the valley of Mount Carter, as if waiting for some spectator to ask its purpose, and listen for a voice to issue from its mystery. Then, lifting itself from its base, and melting gradually upwards, it shrunk into a narrow Btrip of beauty, leaped from the mountain summit to the cloud, and vanished.

It seems difficult to connect such a show, in memory, with 'Gorham,'—so hard a name, a fit title for a rough, growing Yankee village. But such is the way the homeliest business is glorified here; such is the way the ideal world plays out visibly over the practical, in all seasons, and every day. Only have an eye in your head competent to appreciate the changes of light, the richness of shadows, the sport of mists upon the hills, and you can look up every hour, here, from the rough fences and uncouth shops of Yankee land, to the magic of fairy land. While that show was in the height of its splendor, I asked an old farmer, who was hauling stones with his oxen, what he thought of it. He turned, snatched the scene with his eye, and said indifferently, 'It's nice, but we often have 'em here; gee-haw, woo-hush!' Yes, that's just the truth. 'We often have 'em,'--often have the glories of the Divine art, passages of the celestial magnificence, playing over our potato fields; therefore the us pay no attention to them,—count them as matters of course, keep coolly at our digging, and wait for something more surprising to jar us from our skepticism, shatter the crusts of the senses, wake us to a feeling of mystery, and startle us, through fear, into a belief or consciousness of God.

The iris-pillar suggested the burning bush on Horeb. As I close this letter, that passage broadens to my thought, into a symbol of a mightier truth. What statement is so competent as that to set forth the relation of the Creative Spirit to the universe? In Moses' time, nature, in the regard of science, was a mere bush, a single shrub. Now it has grown, through the researches of the intellect, to a tree. The universe is a mighty tree; and the great truth for us to connect with the majestic science of these days, and to keep vivid by a religious imagination, is, that from the roots of its mystery to the silver leaved boughs of the firmament, it is continually filled with God, and yet unconsumed."

At the commencement of this chapter we alluded to the beauty of the drive from Bethel to the hotel in Gorham. One of the prominent resources of a visitor who stays a week or two at the Alpine House, is a ride of ten or twelve miles down the Androscoggin on its right-hand bank, through Shelburne to Gilead, and then up the river on the easterly bank, crossing it again at Lead-Mine bridge. This drive can be taken before sunset on a long summer day, by leaving the Alpine House just after dinner. And no drive of equal length among the mountains offers more varied interest in the beauty of the scenery, the historic and traditional associations involved with the prominent points of the landscape, and the scientific attractions connected with some portions of the road.

In Shelburne, a small village six miles below Gorham, the driver will point out the remains of a boulder, which, before it was blown for use on the railroad track, overhung a ledge that has received the name of " Granny Star bird," or as it is sometimes spelled, " Granny Stalbird." She was the first woman who climbed through the great White Mountain Notch, from Bartlett,—a feat which she accomplished in 1776, on her way to Dartmouth (now Jefferson) to serve in the family of Col. Whipple. Many years afterwards, when a widow, she became very skilful as a doctresses, and often travelled great distances on horseback to visit the scattered settlers in their sickness. When she was very old, she was sent for to visit a sick person below Shelburne, but was overtaken in the night by a tremendous thunderstorm. The rain and wind were so furious that it was impossible for her to keep the road against it, and she drove her horse under the boulder that overhung this ledge, and stood by him, holding the bridle, all night. The wind howled frightfully around her, and the lightning showed her rivulets tearing across the road to swell the Androscoggin; but the hardy old heroine faced it without dismay, and did not leave the rude shelter until noon of the next day, when the storm abated. The builders of the Grand Trunk Railway through Shelburne ought to be indicted for blasting that rock, which belonged to the poetry of the mountains, when any common granite of the neighborhood could as easily have served their prosaic needs.

The history of Shelburne, as of Bartlett and Bethlehem, startles us with the records of suffering which the pioneers in the mountain valleys were willing to undergo in establishing homes there. In 1781, a man, with a wife and three children, moved into Shelburne when the snow was five feet deep on the ground, and the Androscoggin was a bed of ice. The mother carried the youngest child, nine months old, in her arms; a boy of four and a girl of six trudged by her side. Their shelter was a wretched cabin with just enough rough shingles laid across some poles on the top, to cover a space large enough for a bed. Their cow was provided with a large square hole in the snow covered with poles and boughs.

The stories of the ravages of bears and wolves in the neighborhood of Shelburne are more striking than those recorded of any other portions of the mountains. On the drive from Gorham to Gilead, the wagon passes a portion of the road where a pack of wolves attacked an Indian, and killed and devoured him, but not till they had lost seven of their starving band in the encounter; and to their other afflictions, the early settlers of this neighborhood were troubled, as those in the Bartlett Valley were not, by Indian invasions. They experienced not only the hardships of isolation and cold, and the plunder of wild beasts, and the ravage of mountain torrents, and the desolation of freshets, but they knew the terror of the war-whoop, and some of their number felt the scalping-knife and tomahawk, as well as the horrors of Indian captivity. The last of the outrages by the savage tribes in New Hampshire broke upon the settlements along the Androscoggin above Bethel. In August of 1781 a band of Indians made an attack upon Bethel, and after plundering some of the settlers, and taking others with them as captives, came up through Gilead, murdered one of the hardy settlers there, robbed the cabin of the family that had moved into Shelburne on the snow, and carried their prisoners by Umbagog Lake into Canada. When the pooi captives were so worn down with the march through the wilderness, and the loads which the savages laid upon them, that they were ready to faint with fatigue and hunger, the brutes would broil old moccasins of moose skin, tainted by the heat, for their food. One of the party who escaped describes the hideousness of a war-dance in which the Indians disported themselves, in one of the rocky passes through which they were taken. He says, “It almost made our hair stand upright upon our heads. It would seem that Bedlam had broken loose, and that hell was in an uproar." During one of the carousals the Indians amused themselves with throwing firebrands at a Negro called Black Plato, whom they set up as a mark. The man who gives us this account returned to the old neighborhood on the Androscoggin, and lived many years to tell of the hardships of the first settlers, and to see pleasant villages and fruitful fields adorn and enrich a large portion of the valley, through which he and his party were hurried in 1781.

And yet no Indian tragedy is so frightful as the civilized one which is connected with Gilead below Shelburne, and whose date is as recent as June, 1850. Here a Mr. Freeman lived, with a young and beautiful wife and three children. He was a blacksmith, and was employed in the service of the company that were building the railroad from Portland to Montreal. A contractor on the railroad boarded in his family. This man succeeded in alienating the affection of the young wife from her husband, and soon after left the village for New York. The young husband, who was passionately devoted to his wife, found very soon that she had lost all interest in him and in her children. At last, after insisting on a divorce, to which he would not listen, she told him that she should leave his house, and commenced preparations for a journey. A trunk arrived, which Mr. Freeman intercepted, in which he found beautiful dresses and jewelry for his wife, and a letter from the contractor making an appointment to meet her in Syracuse in New York. Mrs. Freeman did not learn of the arrival of the trunk or letter. But she still insisted on leaving her husband, and even informed him on what day she should depart. On the night previous the young husband sat up very long in conversation with his wife, and after she went to her chamber, he left the house. But who is that peering into the window when the light is out, and all is still? About midnight, the piercing shriek rose from her room, " I am murdered!" She was found with her arm shattered, and her head wounded by a charge of buckshot, that had been fired through the window from a musket which had evidently been aimed with care at her heart. "It was my husband," she said to those that gathered in the room. "And will he not come? Oh, George, my dear husband, shall I not see him to be forgiven?" She died before dawn, without any reproaches for her murderer, and with his name on her lips. Many hours after, the husband was found dead, about a mile from his house, and in his hand the fatal razor that had relieved his agony. The tragedy was deliberately planned; for in his house were found letters that contained directions in regard to his children, and the disposition of his property.

Let us drive now across the river, with the horses' heads towards Gorham again, and make our first halt near the house of Mr. Gates in Shelburne, under the shadow of Baldcap Mountain. If we had time to speak of the view from the summit, which requires about two hours' climbing, we should need words more rich than would come at our bidding. But how grand and complete is the landscape that stretches before us as we look up the river seven or eight miles to the base of Madison and to the bulk of Washington, whose majestic dome rises over two curving walls of rock, that are set beneath it like wings! Seen in the afternoon light, the Androscoggin and its meadows look more lovely than on any portion of the road between Bethel and Gorham, and more fascinating than any piece of river scenery it has ever been our fortune to look upon in the mountain region. The rock and cascade pictures in the forests of Baldcap well reward the rambles of an hour or two. Boarders for the summer, at moderate price, have been taken at Mr. Gates's, and we do not know of any farm-house where the view from the door offers so many elements of a landscape that can never tire.

Information

The above two passages were from “The White Hills” written by Thomas Starr King. The book was stereotyped and printed by H.O. Houghton and Company in 1859. The above passages can be found in the book mentioned above on pages 263-278. The photos included one this page were not original to that book. The first photo shows Berlin Falls and Berlin Mills in 1888. The second shows a drawing of the Abbott House in Milan in 1862. The Abbott House (building in the background) stood on the exact same spot where the East Milan store now stands. In the photo is the Milan town water pump where townsfolk would get their drinking water. Near the pump was where the local and county championship wrestling matches were held. At the time when the original drawing was done by Mrs. George (Irene) Dale, Milan was the metropolis and Berlin a mere way station. In 1862, Hiram Ellingwood was the landlord of the Abbott House. In 1926, the original photo belonged to Civil War veteran, William Blair.